I had the pleasure of attending United Geeks of Gaming’s Game Designer Sessions event last night, and play testing the latest (third) iteration of a game whose working title has always been “workers”. I realized after a couple of games that the rules were a little “fuzzy”, seeing as how they’ve never been formally written down, and decided that some kind of documentation was in order… Hence this blog post. (Half rules formalization, half designer diary.)

Workers was initially conceived as a “born digital” board game with the central mechanic that there are a variable number of “resource pools” in the game, and every round each pool’s count of available resources is incremented by one. The name stems from it being a very light “worker placement” game, with the initial version allowing for only one action taken (worker placed) per turn. I’ll get into the various specific actions available when I go into details about each version of the game below.

The only other shared mechanic for all the versions of the game has been the turn / round mechanism. Each round a starting player is indicated, every player takes an action (or two) for their turn in clockwise order, and then the starting player indicator is passed to the next player (also in clockwise order).

Workers “One”

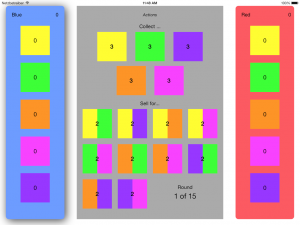

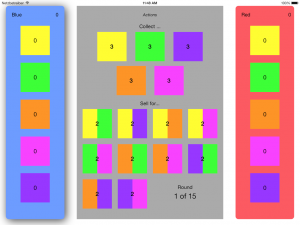

The initial version of this game remains the only one for which there is a (completed) digital prototype. I completed a very quick and dirty app to “prove out” the game mechanics in an evening or two of work and subsequently sent it to some of my TestFlight users for feedback and testing. The prototype was “successful” in that it convinced me more work was needed, but ultimately had quite a few design flaws, which I’ll detail in a minute.

The initial version of this game remains the only one for which there is a (completed) digital prototype. I completed a very quick and dirty app to “prove out” the game mechanics in an evening or two of work and subsequently sent it to some of my TestFlight users for feedback and testing. The prototype was “successful” in that it convinced me more work was needed, but ultimately had quite a few design flaws, which I’ll detail in a minute.

As you may or may not be able to understand from the screenshot, there are 5 available pools of resource (yes, a hard-coded number, even though I knew from the beginning that I wanted it to be variable), as well as hard-coded two-players (with their resource counts on either side of the screen). In the center are all the available actions, and under the main resource pools (which double as buttons for taking the corresponding collection actions) are action buttons for selling each combination of two resource. This version has a selling mechanic whereby you can sell pairs of different-colored resources for the value shown on each pair. Between rounds, not only do the number of resources in each “pool” increment, but the point values for selling each combination are also incremented every round. When a player took a selling action they automatically sold all possible combinations of the two resources for the point value shown. (So if they had 3 green and 2 blue, and took the green/blue selling action when it was worth 5 points, the would end up with 10 points and 1 remaining green resource.) After a sale action, the value for that combination is reset to zero.

Available actions (one per turn):

- collect all of one resource pool

- sell a combination of resources

The game lasted a set number of rounds. (15 here, although I experimented with different values.)

Reasons this version is a failure:

- Replayability: essentially this game played the same no matter how many times you played it. This was pretty boring and led to an…

- Optimal strategy: it turns out, the best way to play this game is to keep collecting resources, whatever pool has the most, until the last two or three rounds of the game, then sell for the highest possible point combination. Boring and stupid. I could possibly mitigate this by capping either point values for selling, or total number of resources, either per player or per pool. Ultimately I never implemented either, and instead moved on to working on…

Workers II

The next version of the game was conceived to “solve” some of the design problems in the fist game by adding variability (via a game board), as well as removing the complex in-game scoring (the entire “selling” mechanic). I don’t remember whether removing in-game scoring was a goal in and of itself, or whether it was primarily meant to facilitate paper prototyping. I took this version to my first Game Designer Sessions meetup, (quite a number of months ago). The game was played at that time with decks of cards with different colored backs for each resource pool.

The “game board” consists of an empty grid at the beginning of the game. Grid dimensions (as well as “number of resource pools”, “starting player resources”, and “starting resources in each pool”) are meant to be variable for each game.

Scores weren’t known/calculated until the end of the game, when all the spots in the grid were filled with resources. I played with a couple of formulas for scoring (see below), but in general, I wanted the more groups and the larger the groups to have higher point values at the end.

Available actions (again, choose one):

- take a pool of resources

- play a single resource from your resources into the game board

Problem:

- One issue became evident right away, and that was lack of incentive to be the player who plays onto the game grid. After one play test, the player who sat back and hoarded resources was the clear victor. If I remember right, I believe we played a second game after the first and changed the “play on the board” action to take the resource from the pool rather than from your hand. Additionally, you got to take one resource from the pool into your hand as part of that action. I came up with another possible solution on the fly last night.

Workers III

The version I brought last night had basically one new mechanic: Every player started with a “x2” (times two) card face-up in front of them. There were two ways you could use this card, but when you did, you turned it face-down, and those actions were no longer available to you. I also play tested this version of the game with colored cubes for resources, which I felt was more visible (at a glance) than had been the case with using decks of cards, and had the added benefit of keeping the game board size considerably smaller. (I drew the game board out as well as “spots” for 4 resource pools on a single sheet of graph paper.)

Possible actions:

- take all of one pool of resources

- place a cube from your resources onto the game board

- use your “x2” action to increase the subsequent pool increment by one additional cube per turn (this could stack if multiple players did it)

- use your “x2” action to place a cube on top of a cube already on the game grid (increasing the size of that group by one without taking up a spot on the board)

We played a relatively quick game with 4 players, 4 resources, and a 4×4 grid, but less than halfway into the game I remembered the problem discovered in the playtesting of Workers II. I let the game play out, but suggested we play another game where you take two actions per turn, but your second action has to be a placement on the game board. One player left, so we played 3-players, 4-resources, on a 4×4 grid, but everyone started with one of each resource. I feel like this went pretty well, but still “needed something”.

Possible scoring mechanisms for multiple variable-sized groups:

- group-size times group-size added together

- group size added together times number of groups

- Fibonacci values for each group totaled, times number of groups

I have lots of ideas for Workers IV. I’ll post back here when I get a chance to try any of them out!

This idea came, originally, hot on the heels of a renewed interest in pyramid games because I’d helped conceive and design these

This idea came, originally, hot on the heels of a renewed interest in pyramid games because I’d helped conceive and design these