When you consider some of the game design imperatives for mobile games — playable in short bursts, interruptible, simple touch controls, UI that fits on a small screen — you may not immediately think that board games are a good fit for the medium. After all, many board games are an all-evening affair, require complex strategies, and cover the dining room table while they’re being played. But there are several reasons that board games are extremely popular on mobile, even games without the marketing budgets and brand recognition of Monopoly or Chess.

First, it should be noted that these are games with an existing fanbase. With a few notable exceptions (see Solforge or Cabals: The Card Game), mobile board games already have a physical version. This means that there is a certain niche fanbase that probably already knows about the game. Quite possibly there are hundreds or even thousands of people who have already played the game and know its rules. Some games already have enthusiastic fans that will help promote a digital version without even playing it.

As anyone with a marketing background knows, the more times a person sees a product, the more likely they are to purchase the product. So a fan of board games might have seen it in their local hobby store or read about it on Board Game Geek. By having a digital version on the market, your game has a leg up on the competition by sheer virtue of name recognition. In fact, this cross-media marketing can go both ways. Notable board game publisher Days of Wonder has been fairly public about the boost in sales their game Ticket To Ride has seen when the app version goes on sale or is otherwise promoted in the app store.

Price point is also worth talking about, as most hobbyist board games cost between $20 and $60, and most mobile apps cost between $0 and $1. A board game conversion application can often command above-average “mobile market value” (usually between $3 and $10) simply because it is being compared to the price of a physical game that is priced considerably higher. To a hobbyist board game connoisseur, picking up a $5 app to “try out” a game that would normally cost much more is quite a bargain. If the game includes a tutorial (as it should!), it might even attract a secondary market in players of the physical board game who can’t, or won’t, be bothered to read a complicated instruction manual.

Design Considerations

All of this should not be interpreted to mean that you can ignore the mobile game design imperatives mentioned at the beginning of this article. In fact, those should be some of your primary considerations when you evaluate converting a board game to mobile. Can you shrink all the information onto a 3.5-inch screen? Can you adequately distill the strategies and experiences of playing that particular game into a single-player experience, and will that experience still be fun? Sometimes the answer to that last question is only maybe, or flat out no, but mobile has another compelling attribute that will allow the game to still be worth making: always-on internet! This means it is perfectly possible to make a mobile game that is multiplayer only. There have been some really successful examples of this, (Words With Friends, for example). Another important question is whether the game can be played asynchronously. What I mean by this is: can each player take their turn without needing the input of the other players? If so, this allows for non-realtime (asynchronous) multiplayer and vastly simplifies the implementation of single-device multiplayer.

I would still recommend you include a single-player experience if you can swing it. The main reason for this is related to the cross-pollination I mentioned earlier between physical and digital. Folks who already own a game will have less reason to pick up a digital version if it is multiplayer-only. Sure, they can play against strangers and over long distances, but it is incredibly compelling to be able to play a board game you enjoy without needing to wrangle up several friends to do so. Some mobile board game publishers claim that their usage stats also show more single player games played than multiplayer, but that is highly anecdotal evidence.

Another question to ask is: does anything need to change when going from physical to digital? Should you use the art from the original board game? (If you can, the answer to this one is absolutely yes.) Obviously, you don’t have little wooden bits to move around, but of course you could simulate those. What if the wooden bits in the game are just counters? Would it make more sense to just show the number they are meant to represent instead of showing the pile of wooden bits? Anything that can be represented numerically is something you should contemplate.

I’ll illustrate this with an example from one of the first (and still one of the best) iOS board game conversions, Carcassonne. Carcassonne is a tile laying game, where on your turn, you have a random tile to play. In the physical version, you randomize by making face-down stacks of tiles or by pulling one from a bag. Theoretically, you know how many tiles there are left “in the bag” (and even what kind they are) by counting the ones already played on the table. In practice, that’s rarely something anyone figures out when playing the physical game. Yet, in the digital conversion, the developers chose to show a list of all the tiles in the game, with the number remaining of each type clearly displayed. This simple inclusion immensely changes gameplay because players will spend less time trying to determine whether or not a particular tile will be available to them later in the game. This allows for a much more strategic playing of the game.

Final Thoughts

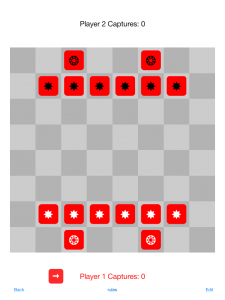

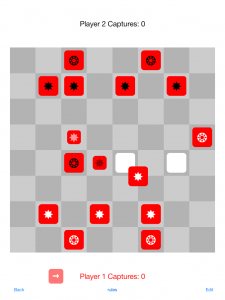

I don’t have space here to go into all the nuances of licensing a board game property for mobile conversion, but I will say that you can bet most of the more popular games have either already been licensed, or have some other reason for remaining unlicensed. There are thousands of board games, however, and there are many, many diamonds in the rough. Likewise, I could write an entire article about UI considerations. How to best represent physical components on a touchscreen device is question that has been answered many different ways already, and only a few great games have really nailed it.

A few board games have now been released simultaneously with their digital counterparts. Marketing a board game is not so different from marketing a video game, and platform dominance applies to both. There may come a time in the not so distant future when we expect these simultaneous releases. Perhaps someday, digital “conversions” will not be considered “conversions” at all, but rather, just another way to play the game.

Note that I originally wrote this article for the IGDA Perspectives Newsletter, and it was posted at the end of November along with the following bio (which I also wrote, just FYI).

Martin Grider has been developing iOS applications since late 2008, when he launched his first application ActionChess, a Chess and puzzle game mashup. At the end of 2012, he developed and helped launch For The Win, an iOS board game conversion for well-known board game publisher Tasty Minstrel Games. Martin is passionate about mobile game development as well as game design for both video games and board games. He is a proud member of the IGDA, where he has presented for the local Twin Cities chapter on iPhone Game Development, Mobile Game Design, and his own mobile games.