2022 was the 4th year in a row that I kept track of all the games I played. This is the 4th recap I’ve written on or around new year’s, and I’ve only just created a category for them if you care to go have a look back through the others. I hope to keep up this tradition as long as I’m alive. But no pressure.

My Games Played in 2022

I won’t write so much this year about my method of keeping track. Suffice to say, it’s a “manual” collection, so obviously it has its flaws.

First, the numbers.

- unique game titles: 352

- days I logged at least one game played: 365

- game titles logged only once: 193

- journal entries about specific games: 30

Top 10 games

(by number of days they show up in the log)

- Flow Free: Sudoku: 244 days

- Good Sudoku: 186 days

- Picross s7: 144 days

- Picross s8: 83 days

- Picross s genesis: 67 days

- 7 wonders architects: 55 days

- New Frontiers: 49 days

- Jump Drive: 49 days

- Innovation: 49 days

- Azul: 41 days

Top 10 games, including platform, without BGA games

(…and making a special check for days I played Picross.)

- Picross (Switch): 297 days

- Flow Free: Sudoku (iOS): 244 days

- Good Sudoku (iOS): 186 days

- Elden Ring (PS5): 35 days

- Cell to Singularity (iOS): 31 days

- Really Grass Cutting Incremental (web): 29 days

- Vampire Survivors (Steamdeck): 23 days

- Jetpack Joyride 2 (iOS): 18 days

- Borderlands 3 (PS5): 18 days

- Horizon Zero Dawn (PS5): 14 days

Observations

I stopped playing both Good Sudoku, and Flow Free: Sudoku after getting the “played for 365 days in a row” achievements. I don’t expect either of them to show up on next year’s list. Obviously this list has a lot of Picross in it, because I still mostly just play that when I’m doing my 20-40 minutes of cardio in front of the TV. I do let myself skip the workout on occasion, and it’s definitely more likely if I’m feeling sick. I think that explains most of the days I didn’t play it.

[Update/Addition on Jan 2nd]

My friend August asked “Do you have a favorite game this year and why is it Picross?” I realized that kind of analysis is maybe something this post was missing, so here is my response.

I do love Picross, but I’m not sure I’d even put it in a top 10 list. It’s my go-to workout game because it fires all the brain cylinders (meaning my workout passes without the clock-watching that ensues otherwise), and does that without any need for spacial awareness that can cause me to fall off the trampoline.

My favorite of the games I played in 2022 is probably Elden Ring (35 days, PS5) just because of how sucked-in I became even as I lambasted it. I wrote several journal entries about it, and ended up loving it in the end, even as I reached a saturation point where I decided I never need to play it again.

I also loved Stray (9 days, PS5) and Horizon Zero Dawn (14 days, PS5), both of which I played to completion in 2022.

Probably my favorite indie game of the year was Tinykin (2 days, Xbox). Super interesting that my log only shows that I played Tinykin on two days! I definitely beat the game, and even remember stretching out my playtime by intentionally veering toward completionism toward the end. (I may have just forgotten to log it some days? Or maybe it really is that short.)

I also really liked Nobody Saves the World (10 days, xbox).

I did have a phase this year post-steamdeck where I got back into action puzzle games, and played a lot of those for a few weeks. Notable favorites are Lumines (8 days), Petal Crash (7 days), and Mixolumia (6 days). I only logged Tetris Effect on 5 days (probably during that same period). Note that none of those games were “new to me” in 2022 except for Petal Crash. Just like books, I tend not to return to games unless I remember really loving them, so those are all favorites.

Platforms by number of games

- BGA – 80 games on 231 days

- Playdate – 56 games on 54 days

- iOS – 53 games on 310 days

- Steamdeck – 46 games on 90 days

- Web – 30 games on 43 days

- Tabletop – 23 games on 31 days

- Xbox – 20 games on 69 days

- PS5 – 13 games on 84 days

- Pico-8 – 12 games on 8 days

- Switch – 11 games on 298 days

- Quest – 7 games on 7 days

Platforms by number of days

- iOS – 53 games on 310 days

- Switch – 11 games on 298 days

- BGA – 80 games on 231 days

- Steamdeck – 46 games on 90 days

- PS5 – 13 games on 84 days

- Xbox – 20 games on 69 days

- Playdate – 56 games on 54 days

- Web – 30 games on 43 days

- Tabletop – 23 games on 31 days

- Pico-8 – 12 games on 8 days

- Quest – 7 games on 7 days

Platform Observations

Poor VR. I never pay attention to it anymore. (I didn’t even preorder the PSVR2… I’ll buy it if it looks like any of the games are going to be amazing, or if they suddenly give it backward compatibility with all the OG PSVR games.)

I was really excited about the Playdate for a while there. I’ll talk a little more about that later. I’ll probably get back into it again if they release a Season 2 of games.

The Steamdeck is now my favorite gaming platform. I don’t have any free HDMI ports on my TV, or I’d be playing more of it there, probably, but in the mean time I do very much enjoy it as a handheld. It obviously helps that I have a library of over a thousand games to choose from on it. (Built up over years and years of bundles and various sales, but also I feel no qualms about paying “full price” for any game that I feel moderate confidence I’ll find the time to play.)

BGA

Board Game Arena was where I did the majority of games playing this year. My game log says 80 games (unique titles) played on 231 days, which is obviously wrong on both counts. I was initially surprised it wasn’t more days, but then I realized that’s definitely a consequence of how I’m doing my logging. I currently only log BGA games on the day they have been completed. This means if I play a single game (of Azul, for example), but the turns stretch out over a week, it would only get one entry, even though I played my turns every day. Last year I logged every day that I took any turns in that game, but it was too much logging, and I felt like it gave too much weight to async games.

For 2023, I’m definitely going to change it up again, but I’m not sure exactly how. I might actually just log that I played some turns on BGA, and not worry about what games. Or maybe I’ll try and just log any game that I’ve not yet logged that year, so I have a complete list.

It’s definitely less important, because BGA does a great job keeping track for me. You can see all my BGA stats at this link: https://boardgamearena.com/gamestats?player=1486543&opponent_id=0&start_date=1641016800&end_date=1672466400&finished=1

- BGA “tables” (total number of games played): 614

- Games won (victories): 328

BGA Most played games

- 7 Wonders Architects: 77 games

- Jump Drive: 62 games

- Innovation: 55 games

- New Frontiers: 51 games

- Azul: 47 games

- Splendor: 38 games

- Stone Age: 22 games

- Space Base: 18 games

- Race for the Galaxy: 16 games

- King of Tokyo: 15 games

- 6 nimmt!: 15 games

- Gizmos: 15 games

- Nova Luna: 10 games

- Oust: 10 games

- Caverna: 9 games

- Thrive: 9 games

Caverna and Gizmos get special shout-outs, because both showed up relatively late in the year. Gizmos is definitely in my top 10 games right now, and when it first showed up on BGA, I was playing so many games of it that I kind of burned out on it, and had to stop for a few weeks. Now I’m back to a regular game or two of it going at all times. Same with Caverna, though it’s not as high on my want to play list, it seems like it is for everyone else I play BGA games with on the regular.

I think 7 Wonders Architects and Jump Drive are only at the top because they’re very short games, and my friends Mike and Jason both like 7 Wonders a lot, so we have a continuous game going with the three of us, and we finish a game once or twice a week, I’m guessing.

My Game Design Journal in 2022

My game design journal had 40 new entries in 2022. (Sadly there were 4 months with only one entry, including December. And 5 months with only 2 or 3 entries.)

Of those entries –

- 2 were from dreams (providing some evidence my subconscious is still thinking about new game ideas, even when my conscious mind can’t be bothered)

- 11 were continuations – additional thoughts or implementation notes related to previous ideas

And the most disappointing stat:

- only 1 entry resulted in a new (digital) prototype

There were a few entries that could have been flushed out into new physical game prototypes, but my guess is that I played physical games much less this year than in the past. (Although 31 days doesn’t seem like that few, tbh.) Anyway, I think a significant percent of my interest in designing physical games has waned with the realization that I just don’t play games physically that often anymore. This is a bit weird, because I play digital versions of physical games literally every day, but it’s something I’m pretty sure my brain is doing.

Game Development

My current work schedule allows for somewhere between 3 and 12 hours spent working on games per week. When motivation is low (as it has been most of this year), it’s usually on the lower-end of that range.

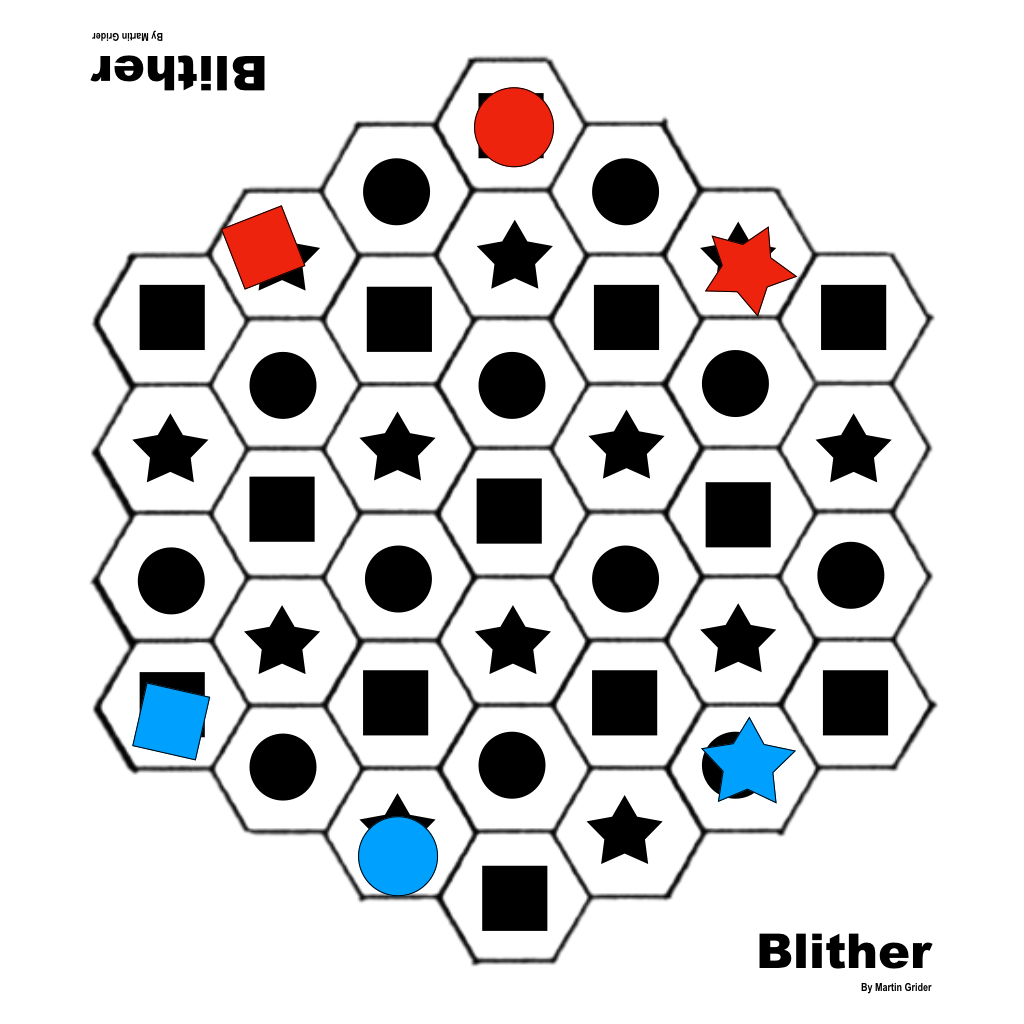

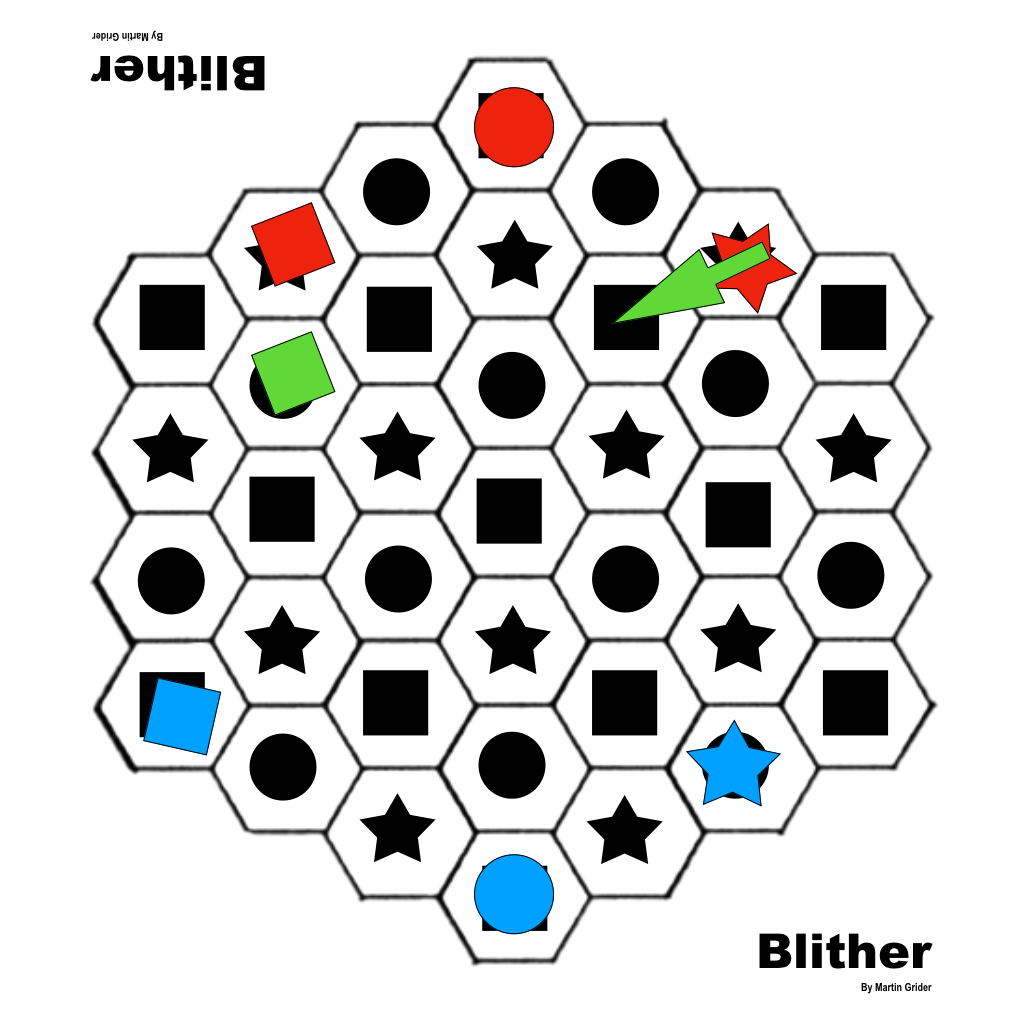

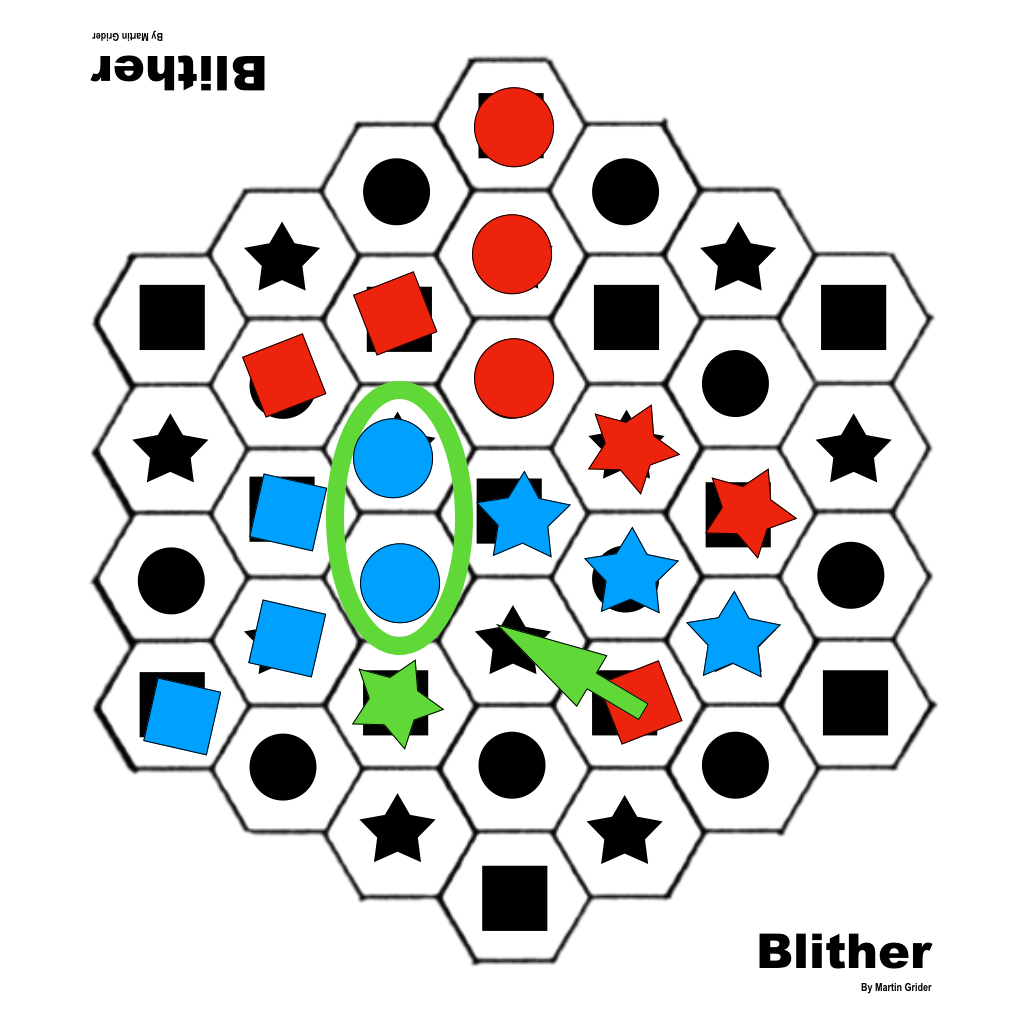

Mostly, I spent this entire year working on a digital version of Blither, an abstract strategy board game I designed a couple of years back. I’m happy with Blither’s design, and a few times I’ve considered trying to hand it off to publishers. I think it could work particularly well with some kind of animal/nature theme, but so far at least, the digital version is just all geometric shapes.

Swift for Game Development

A significant amount of the effort that I’m counting toward Blither’s development has actually been spent less on the game itself, and more on the toolchain for writing games in Swift. I spent several weeks – maybe as much as a month of my development efforts – just exploring cross-platform strategies for Swift and game development. The primary take-away is that it is relatively “easy” to write a swift “wrapper” for projects written in C, so there are many. Of interest, both Raylib and SDL (both of which exist in the cross-platform game development “space”) each have at least a few of these projects on GitHub. Unfortunately, while it is easy to write these wrappers, getting them to a state where they are easy to use requires more effort, and in my estimation, that narrows the selection considerably. “Easy to use” might be assumed to include “well documented”, but sadly it does not, and none of the projects I found would qualify there. Furthermore, lack of documentation definitely means lack of instructions for how to actually publish a project using any of these libraries across various platforms and OS targets. For a while, this was definitely my objective. Pick a lib, write a simple game, and document the hell out of getting it running on at least: MacOS, Windows, iOS, and Android, using the same codebase.

Unfortunately, of the aforementioned Raylib and SDL library wrappers, Raylib itself doesn’t support iOS (at least without plugins/modifications), and SDL is slightly more difficult to use, and possibly as a consequence, in general the wrappers I found for it were not as far along, or anyway, not as easy to use.

Another related project is re-writing my generic game library in Swift. There was never all that much code to GGM, so the actual rewrite was never the hard part. The original GGM used UIKit for rendering, so there is a Swift version that does that, but also now there is a version that uses SpriteKit, and a (not-quite-flushed-out-yet) version written in “pure Swift” without any rendering included. Ideally, I’d use that version to write “plugins” for platform-specific rendering engines, and this could be another path to writing cross-platform games. That last version, while unfinished, is already significantly more code than the others, and I got a bit hung up on what its internal API should look like. The other versions don’t really concern themselves with non-game UI, but this one would have to, and that’s a big old can of worms that I’ve barely opened.

Hex-Grids

Speaking of GGM, the original library supported hexagonal grids – it was used for the Catchup app – but the way it implemented them was very specific to the Catchup codebase, and felt a bit tacked-on. So when I went to add that detail to GGMSwfit, I got sidetracked a bit on what hexagonal grid coordinate types to support, and how many hexagonal grid shapes to make it easy to create. I dug around a bit, and ended up playing a bunch with a “pure Swift” library called Hex-Grid (https://github.com/fananek/hex-grid/) that does pretty much all of the hexagon-specific stuff that I wanted GGM to do, and I contributed to that library a bit. Mostly, I wrote a demo app that uses SpriteKit and allows you to visualize grids of arbitrary size and shape and swap out their coordinate types on the fly. (This also helped expose a few bugs in the lib.)

The current app version of Blither doesn’t use any flavor of GGM, instead it uses this Hex-Grid library, and it is also using SpriteKit for drawing. This means it can only target platforms where SpriteKit exists. (iOS, iPadOS, and MacOS, I believe. But – so far at least – I would need to make some not insignificant changes to make Mac Desktop work.) I’m still toying with the idea of making an abstraction layer for the SpriteKit-specific code, so code could be shared with other platforms.

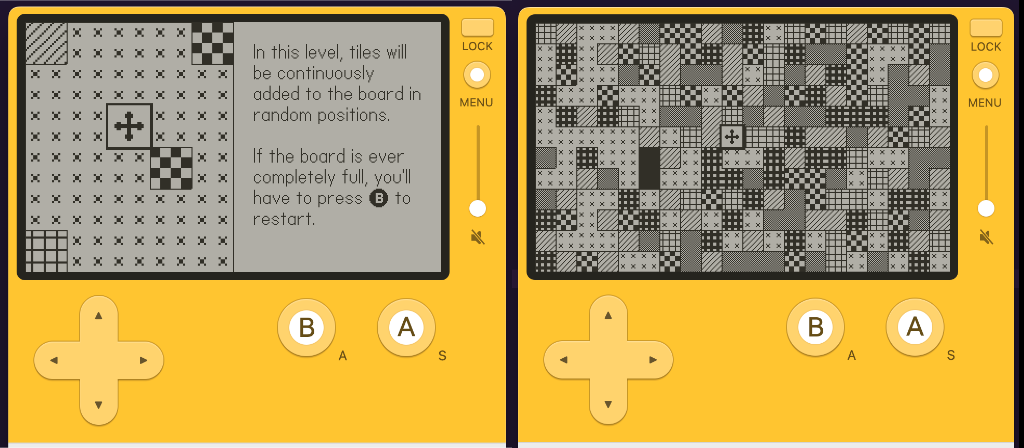

Playdate

Another project I worked on this year was a match-4 game for the Playdate called Matching Machine (https://devforum.play.date/t/matching-machine-devlog-and-demo/7682). I “released” a version on the Playdate developer forums and then promptly lost interest in finishing it up. This year’s MinneBar happened while I was working on it, and it was the first time I’d been to an in-person conference in a few years. I gave a talk there about Playdate development in general.

Non-Game Development

Conferences

MinneBar was great (as usual), and while my family is under no illusions that the COVID-19 pandemic is over, I still ended up going to two other in-person conferences this year: Eyeo and FOSS-XR. Eyeo has been one of my favorite conferences whenever I attend, and this year’s conference came with the sad announcement that it will probably not continue – at least in its previous form – going forward. I somewhat regret not making more contacts and acquaintances while attending over the years, but it’s an intimidating crowd full of amazing digital artists and creative coders. I brought Thrive to one of the evening events this year, and introduced it to lots of new players, so it’s not like I was entirely invisible.

Foss-XR was a surprise to me, having found out the week before that it was going to be held only blocks from my apartment in downtown Minneapolis. I didn’t know what to expect, and after a rocky start with poor AV, ended up really enjoying the experience. I also reported on it a couple of weeks later at the only in-person MNVR&HCI meeting I attended this year.

Webdev

I haven’t done any REAL web development since around 2011 or so, but I still host a half-dozen or so websites (including this blog). Many of those are using WordPress, and I’d love to move those to Jekyll, or (maybe ideally) something similar to Jekyll but written in Swift. (Publish is the only one of those I know about, but I haven’t done any due diligence yet.) I guess I’m officially stating this as a goal for 2023. I did already export some blog content, and then import it into Jekyll at some point in 2022, but I would probably have to do that again if I were going to migrate “for real”. (I helped out with a transition of this sort when the IGDATC website moved from WordPress to Jekyll, but I didn’t personally handle the export/import.)

I also got really into reading about ActivityPub after moving from Twitter to Mastodon in 2022, (my mastodon account is @grid@mastodon.gamedev.place) and I thought seriously about starting a project to support ActivityPub/Mastodon interop from Vapor. I have played with Vapor a few times since I found out about it, and did so again for an afternoon when I was thinking about this. It’s more likely that I’ll just create some static files to point a domain or two to various Mastodon accounts, but I haven’t even done that yet, so it’s obviously not a huge priority for me. I do think federated social networks are here to stay, and I hope the trend of user-owned content creation continues. I will help it along if I can.

AI

Like everyone else, I was gobsmacked this year by text-to-image AI. I spent a not-insignificant amount of time reading about the technology, and even went so far as to install Stable Diffusion on my M1 MacBook Pro. Initially I wanted to use it as a pipeline for making game art, but the many important discussions happening around the ethical implications have me cooling my jets a bit. I did also use Midjourney to generate character portraits for a D&D campaign, and that was an easy win. I will definitely continue to keep my eye on the developments related to this technology going forward.

Contracting

A few years back (even before the pandemic) I realized that working on games professionally left me without interest in working on my own games, so I re-focused my contract work back on native iOS. I am still waiting patiently for Apple to release a headset, and hope to find some crossover contract work when that happens, but until then, my bread-and-butter is mostly won with plain old iOS app development. I’m very happy with my current contract, and it should take me at least partly through 2023. There is other work on the horizon (they would like me sooner than later – and I appreciate their patience), but for now I’m trying to focus mostly on one contract at a time.

Something I haven’t talked about publicly in a while is how much time I’m devoting to contract work versus my own game development. But to talk about that, I need to first talk about how much time I spend working. Period. It’s a hard number to pin down, because there are several contributing factors. How many hours do I work each day? And how many days? How many of those are billable?

In general I aim to bill my clients for 20 hours per week. Ideally I would be working a 40 hour week, and that would leave 20 hours for gamedev, but it’s hard to say whether that’s actually the case. It’s only possible if you include hours outside of my normal workday, because for the last few years those tend to only be 6 or 7 hours long. Previous to this year, I’d have said it was very common for me to put in some extra hours in the evening after the rest of my family has gone to sleep. This year, I would say that’s definitely been the rare exception rather than the norm. So my guess is that I’m putting in a work week that’s more in the order of 30 hours than 40. However, there have been a lot of saturdays and sundays that were essentially a normal workday for me, (but always devoted entirely to gamedev), so maybe it averages out. Again, it’s really hard to say, because I don’t track the time that isn’t billable.

Generally on days when I get started working on a game project, it’s rare that I will want to stop working on it and go back to contract work, so that day is usually then relegated entirely to gamedev. For this reason, I usually try and always start my work day with contract work. Then if I’m itching to do some gamedev, I’ll switch to it later. But I don’t give myself that restriction if I’ve already billed 20 hours that week. That used to mean that most of the time Fridays were days for gamedev, but pretty regularly (this year anyway), I’ll be in the middle of some client task, and want to keep working on it more than I want to switch tasks and work on a game project. So usually my gamedev is on the weekends, with the occasional Friday afternoon thrown in for good measure.

Contracting gives me the freedom to turn off the clock whenever I want, and take an hour or an afternoon off just to run some errands or even unplug or play some video games. It’s relatively rare that I take a whole day away from “work”, but it’s very common for me to take an hour here and there, which has the consequence that it’s very often Friday morning and I haven’t yet hit my 20 hour mark. But I really do enjoy what I do. I can’t really count the number of times in the last 3 years I’ve remarked that my job is one of the things that’s keeping me sane. I find programming to be a much-needed catharsis when the rest of the world is an assault of illogical thinking and frustrating politics. I get to solve puzzles all day, and that’s not an exaggeration. And as anyone who knows me will attest: I do love puzzles.

Book notes

I’ve been keeping a log of books I read much longer than the log of games. The first iteration of this was just a text file that followed me from computer to computer from sometime in high school until several years after college, when unfortunately I fell out of the habit. Then I used LibraryThing for a couple of years, and then Goodreads for at least the last 10 years or so. (I’d really like to switch to Bookwyrm, and I have an account at bookwyrm.social, but I haven’t fully transitioned yet because their importer has been turned off due to overwhelming demand on resources. I did try to convince a friend to set up a new instance for us, but that hasn’t happened yet.)

Last year I marked 64 books read on GoodReads. Mostly I just read science fiction (and fantasy, and graphic novels, which I’ll admit are such easy reads that they make me look like a more voracious reader than I probably am), but a few days ago, I wrote a thread on Mastodon about some of the game-related books in my library that I recommend, and I thought I could link to that thread here.

Notably, the last book included in the thread is one I haven’t marked as “read” on goodreads yet. I’m still working my way slowly through Ben Orlin’s book Math Games with Bad Drawings, which I’ve been meaning to recommend here.

Conclusion

I wish everyone reading this a wonderful new year in 2023!